- Published on

⭐Why do humans hear music in log base 2?

- Authors

- Name

- Anirudh Sathiya

[ Readtime: <3m ]

Recently, I’ve been getting into playing the guitar and, along with it, exploring music theory. So far, my journey has led me to some fascinating facts about music that I found truly intriguing.

One such fact is that we perceive music in logarithmic base 2. That is, the same note in the next octave always has twice the frequency of the original note. In other words, if you pick a set of evenly spaced notes on the piano, their frequencies follow a geometric progression rather than an arithmetic one.

But why is this the case? This question led to more questions than answers. Let’s take a step back.

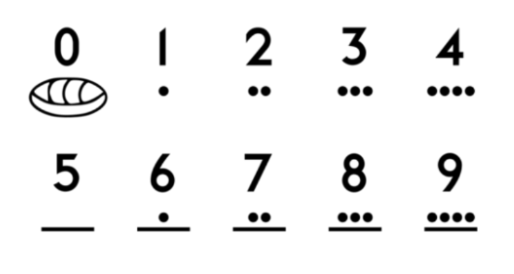

This logarithmic behavior isn’t unique– almost all human senses are perceived logarithmically—brightness, loudness, distance, and pitch. In elementary physics, you might have learned that the decibel system for sound also follows a logarithmic scale. Even in archaic counting systems, numerical notation patterns change after around four, as humans start to struggle with counting when there are more than a few objects.

Ancient counting systems that stop counting linearly after the first few numbers

One possible explanation of these phenomena can be derived from one of the first observations in psychophysics formulated by Ernst Heinrich Weber and Gustav Theodor Fechner.

They noticed that the change in perceived stimulus is inversely proportional to the original stimulus.

where is perceived sense, and is the stimulus.

Integrating both sides:

Here is the constant of integration, which can be determined based on boundary conditions.

Now, we modify for perceived pitch, and for frequency , then:

Hence, we are able to derive that perceived pitch is logarithmically proportional to frequency. Neat. But still, why do we hear in base 2? How come so many cultures unanimously used the same notation in music for every second multiple in frequency?

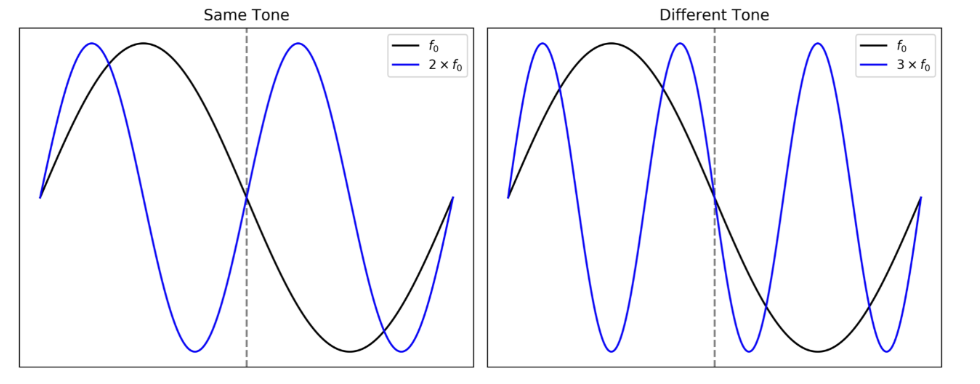

We could also come up with an answer based on the shape of a soundwave, and how we have maximum consonance when the wavelengths are multiples of each other. But how come a frequency sounds closer to than say ?

There is evidence suggesting a neurological—and possibly evolutionary (cited below) basis for perceiving octaves as equivalent. This phenomenon appears to be fundamental, as it is observed in monkeys and other mammals, though it does not seem to occur in certain birds. It has been discussed that primates have a quality called pitch chroma, where the architecture of neurons in our auditory cortex allows us to see multiple octaves of the same note as one “color”. There have also been studies showing certain isolated cultures not able to identify octave resemblance, meaning it might be an acquired skill afterall. Despite all the research in this field, we haven’t confirmed whether it is evolutionary, psychophysical, cultural, or something in between.

Sources / More interesting articles to read than my blog :

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weber%E2%80%93Fechner_law

- https://rss.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2013.00636.x

- https://music.stackexchange.com/questions/108146/why-do-frequencies-that-follow-a-base-two-logarithmic-relationship-sound-the-sa

- https://www.reddit.com/r/musictheory/comments/360ner/why_do_humans_perceive_sound_in_log_base_2/

- http://www.neuroscience-of-music.se/eng7.htm